Driven by winds over the Pacific Ocean, a radioactive plume released from the Fukushima Dai-ichi reached Southern California Friday, heightening concerns that Japan's nuclear disaster was assuming international proportions.

However, the results of testing reflected expectations by International Atomic Energy Agency officials that radiation had dissipated so much by the time it reached the U.S. coastline that it posed no health risk whatsoever to residents.

The U.S. Department of Energy said minuscule amounts of of the radioactive isotope xenon-133 — a gas produced during nuclear fission — had reached Sacramento in Northern California, but the readings were far below levels that could pose any health risks.

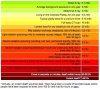

Initial readings from a monitoring station tied to the U.N.'s Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization were about "one-millionth of the dose rate that a person normally receives from rocks, bricks, the sun and other natural background sources," the U.S. Department of Energy said in a prepared statement.

The statement confirmed statements from diplomats and officials in Vienna earlier in the day.