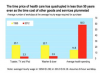

Sorry, that looks blurry, but you get the point.

The article goes on to say:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/chrisc...ost-of-health-care-1958-vs-2012/#5a746dac4910

Of course, health care in 2012 is vastly different and greatly improved compared to what was available in 1958. But the same can be said of other goods and services (Perry, for example, is comparing the cost of an iPod to 4-speed automatic record player).[1] This simple comparison reminds us of three basic truths. In general, private markets tend to produce steadily lower prices in real terms (e.g., in worker time costs) and steadily rising quality. This is exactly what we observe for goods such as toasters, TVs, iPods, washers and dryers. In contrast, while the quality of health care unequivocably has risen since 1958, real spending on health care has climbed dramatically. This isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison insofar as the bundle of goods and services that constitute health care is also much larger today than in 1958. In contrast, even though the quality may be better, a washing machine in 2012 is still a washing machine.[2] If we were willing to rely more on markets in medicine, we might be able to harness the superior ability of Americans to find good value for the money to produce results more similar to other goods.

Second, over time, we as a nation have been able to afford more health care precisely because the time cost of other goods and services has declined. For the same number of hours worked, workers can enjoy the same standard of living even as they allocate more of their working time to purchasing health care. There is nothing wrong with this. The only issue is whether we are getting good value for the money when we buy health care. With only

11 cents of every health dollar paid directly out-of-pocket, I think most of us can honestly say “no.”

Anyone who is skeptical on this point should do the following mental experiment: if I promised to pay 89 percent of the cost of your groceries, would what you buy be different? Most students I ask freely concede that they would buy things they would not otherwise buy and might well pay higher prices even for things they would have bought anyway. The difference between the cost of your weekly groceries when you buy them with your own money (say, $100) and what you spend when someone else is paying most of the bill (say, $150) is not pure waste. There is some added value to you from those extra groceries. But that value cannot exceed the added cost else you would have bought them on your own in the first place. The difference between that added cost and your own estimate of the added value is what an economist would call waste. According to the

Institute of Medicine, we wasted about $765 billion in health care in 2009—about 30 percent of all spending.